Chancellor Rachel Reeves revised the UK’s fiscal rules in the last budget in October 2024, aiming to bolster the government’s credibility with investors and reduce its borrowing costs. The new rules require the government to balance the day-to-day budget (excludes public investment) by the end of this parliament and target a reduction in the public sector net financial liabilities ratio. These measures were largely intended to reassure investors that the UK is committed to fiscal discipline.

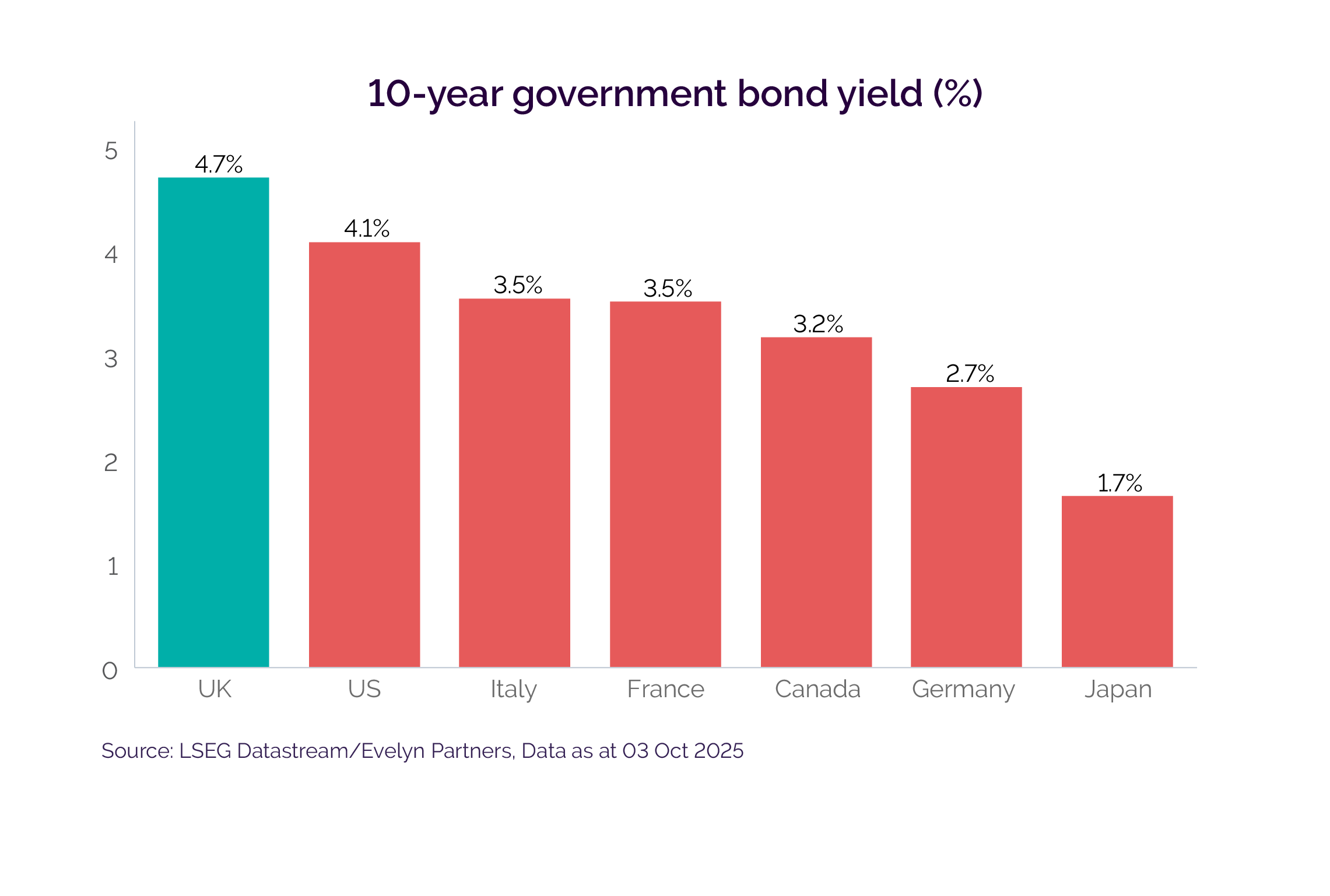

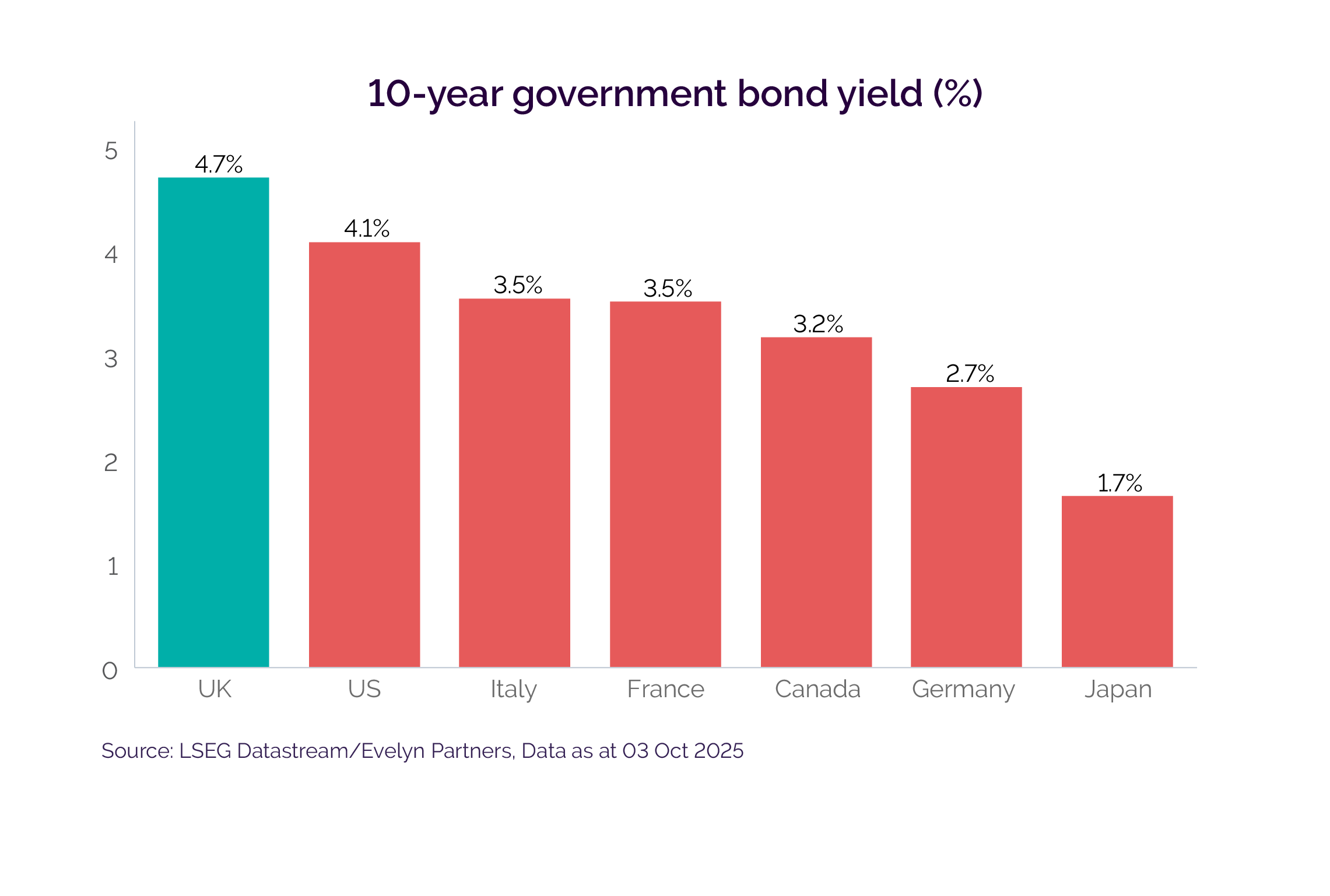

These changes have yet to deliver the intended results. The UK now holds the unwanted distinction of having the highest 10-year government bond yields among developed economies. At the time of writing, the 10-year gilt yield stands at 4.7%—higher than both Italy and Greece, despite those countries having much higher public debt-to-GDP ratios.1

Nevertheless, gilt yields are not solely a reflection of fiscal policy. They also capture expectations around short-term interest rates, inflation, and broader monetary conditions. A similar dynamic is playing out in the US, where investors are increasingly focused on fiscal sustainability, particularly given widening budget deficits. In both cases, markets are sending a clear signal: fiscal credibility matters, but so do inflation and interest rate expectations.

In short, several factors are contributing to increasing cost of UK government borrowing relative to other G7 Nations.

- The UK appears to be trapped in a stagflationary environment, where sluggish growth creates doubts over fiscal sustainability.

- The UK is forecast by the OECD to post the highest inflation rate among G7 nations this year. The Bank of England’s relatively tight stance and persistent inflation pressures have contributed to elevated yields.

- Signs of public dissatisfaction with the government, as evidenced in opinion polls, raise concerns about political stability—an important consideration for gilt investors.

Ultimately, the UK government’s credibility in the bond market is earned through realism, not just fiscal discipline. As such, asset allocators will probably be focused on three main issues in the run-up to and after the budget on the 26 November.

1. The growth outlook

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the UK’s fiscal watchdog, is widely expected to downgrade medium-term growth forecasts. In the OBR’s Spring 2025 commentary, it highlighted that their productivity projections have been revised downward.

Slower growth has immediate fiscal consequences. JP Morgan estimates that if real GDP growth is downgraded by just 0.1–0.2%, it would create a budget shortfall of between £9–£18 billion.2 In essence, the UK could be falling into a self-perpetuating cycle. — as taxes are raised to fill fiscal gaps, the likelihood of recession and further revenue shortfalls increases. This makes the task of fiscal consolidation even more challenging

2. Fiscal headroom

In August, the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, a politically neutral think tank, estimated that the government would need to find £50 billion in savings to achieve a modest £10 billion of fiscal headroom by 2029. This is a challenge considering most government spending commitments were locked in during the summer spending review.

Efforts to find further savings are complicated by internal Labour Party divisions, with MPs rebelling against measures such as means-testing the Winter Fuel Allowance and cutting welfare.

This leaves tax increases as the primary lever to balance the books. However, the Labour manifesto pledged not to raise any of the “big three” taxes—National Insurance, VAT, or income tax—which together account for nearly 75% of total tax revenues.

There will be scrutiny on how the Chancellor can credibly raise additional revenue. Potential options could include closing tax loopholes, reforming capital gains and inheritance tax. However, each option comes with political and economic trade-offs.

3. Political stability

The Labour Government’s popularity has fallen to new lows in recent opinion polls. According to Electoral Calculus, a UK based specialist in election forecasting, if current opinion polls trends continue, Reform UK could win 301 seats—below the 326-threshold for a majority in the House of Commons. Labour would drop to 153 seats (down from 412 in 2024), and the Conservatives to just 51 (down from 121).

There are multiple reasons for the decline in Labour’s popularity. Policies, such as restricting eligibility for the Winter Fuel Allowance and cutting welfare, which subsequently forced U-turns, have not been well received by the public.

The issue of immigration is also an important factor to the electorate. According to pollster YouGov, the public nationally believes that the most important issue facing the country is immigration and asylum, slightly ahead of the economy. Managing immigration has proven difficult for the government: the recent “one in, one out” policy agreed with France on illegal immigration comes with legal challenges and is yet to show clear signs of effectiveness.

Given these polling trends, gilt investors will be watching closely to see if the budget can revive Labour’s popularity. If not, there is a risk of leadership challenges and internal party strife—developments that would further undermine confidence in the UK bond market. For instance, Andy Burnham, the Mayor of Greater Manchester, has hinted at a possible challenge for Kier Starmer’s job. His economic stance of criticising the UK’s dependence on financial markets and proposing £40 billion in borrowing for housing is a concern for investors, where such moves could unsettle bond markets and drive-up gilt yields.